By Colin Houghton

In a recent article by Mark Delucchi and Stanford Engineering Professor Mark Jacobson argued that we don’t need nuclear power, coal, or biofuels. Both argue that we can get 100 percent of our energy from wind, water, and solar (WWS) power, efficiently, reliably, safely, sustainably, and economically.

We can get to this WWS world by simply building a lot of new systems for the production, transmission, and use of energy. One scenario developed takes us to 2030, when we could have… and take a deep breath here…

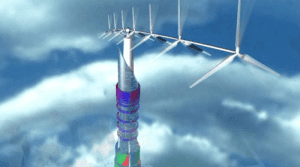

• 3.8 million wind turbines, 5 megawatts each, supplying 50 percent of the projected total global power demand

• 49 000 solar thermal power plants, 300 MW each, supplying 20 percent • 40 000 solar photovoltaic (PV) power plants supplying 14 percent

• 1.7 billion rooftop PV systems, 3 kilowatts each, supplying 6 percent

• 5350 geothermal power plants, 100 MW each, supplying 4 percent

• 900 hydroelectric power plants, 1300 MW each, of which 70 percent are already in place, supplying 4 percent

• 720 000 ocean-wave devices, 0.75 MW each, supplying 1 percent

• 490 000 tidal turbines, 1 MW each, supplying 1 percent.

But even if all this were available to us, the existing transmission infrastructure would be woefully inadequate. We would need to greatly expand this in order to create the large supergrids required to span many regions, countries even continents. The authors say that we would also need to expand production of battery-electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, ships that run on hydrogen fuel cell and battery combinations, liquefied hydrogen aircraft, air- and ground-source heat pumps, electric resistance heating, and hydrogen for high-temperature processes. Many of these new technologies are of course in their relative infancy, and while they may work as a pilot or prototype, may not be economically viable- at least to begin with. What else is needed by 2030 is……of course to reduce demand. The authors suggest we do this by improving the efficiency of devices that use power, and/or substituting low-energy activities and technologies for high-energy ones—for example, more “telecommuting” instead of driving to work.

I guess the ultimate extrapolation of this is that we all work and communicate from our PCs in our homes, and rarely, if ever, meet people face to face. That may require some new thinking in leading and motivating staff, for example. And there will be some jobs that require a worker to travel- manufacturing plants for example, and not least, repairs to wind turbines!

Because this massive deployment of WWS technologies requires an upgraded and expanded transmission grid and acces to that grid by electric vehicles and the like, the authors say that governments need to carefully fund, plan, and manage a long-term, large-scale restructuring of the electricity transmission and distribution system. In much of the world, we’ll need to see international cooperation in planning and building supergrids that span across multiple countries, because many individual countries just aren’t big enough to permit enough geographic dispersion of generators to mitigate local variability in wind and solar intensity.

Given the lack of cohesion and agreement between many soveriegn countries over many issues today, this shouldn’t be underestimated. Look how they are dealing with the global economic crisis! However it’s not all doom and gloom. Ten northern European countries are beginning to plan a North Sea supergrid for offshore wind power. Africa, Asia and Southeast Asia, Australasia, China, the Middle East, North America, South America, and Russia will need supergrids as well, say the authors. Getting countries to focus and agree on such big decisions to bring everything in by 2030 would seem to need some kind of global Paul on the road to Damascus vision that hits world leaders and world opinion, very soon.

The authors go on to give exmaples of the world (or significant parts of it) pulling together to bring off great change. The Apollo program, widely considered one of the greatest engineering and technological accomplishments ever, put a man on the moon in less than 10 years. During World War II, the United States transformed motor vehicle production facilities to produce over 300 000 aircraft, and the rest of the world was able to produce over 500 000 aircraft. In 1956, the United States began work on the Interstate Highway System, which now extends for about 47 000 miles and is considered one of the largest public works project in history. Sceptics may point to the fact that it needs a crisis to spark such single-minded determination to achieve a goal, such as a World War, or a Cold War, or an overwhelming economic requirement. And this was just one country, the United States.

Efficient and Reliable: “A 100-percent wind, water, and solar power system can deliver all of the world’s energy needs efficiently. Jacobson and I estimated the potential supply and compared those estimates with projections of energy demand made by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. We calculated that the amount of wind power and solar power available in locations that can likely be developed around the world, excluding Antarctica, exceeds the projected world demand for power in 2030 for all purposes by more than an order of magnitude. On top of that, Jacobson and I estimate that converting to a WWS energy infrastructure can actually reduce world power demand by more than 30 percent (based on projected energy consumption in the year 2030), primarily because electric motors have less energy loss than do combustion devices.”

The authors are not without feet planted in reality. They realise that no single wind-power farm or solar-photovoltaic installation can reliably match total power demand in a region. But they say it is also true that no individual coal or nuclear plant can either. It’s a given that any electricity system must be able to respond to changes in demand over months, weeks, days, hours and even minutes! A WWS electricity system must handle changes in demand far differently; they face inherently more variability; the maximum solar or wind power available at a single location varies over minutes, hours, and days, and this variation rarely matches exactly the demand pattern over the same timescales. The authors say that a WWS system will need to interconnect resources over wide regions, creating a supergrid that can span continents. And it will probably need to have decentralized energy storage in residences, using batteries in electric vehicles. Also WWS generation capacity should significantly exceed the maximum amount of demand in order to minimize the times when available WWS power runs short. They claim that most of the time, this excess generation capacity could be used to provide power to produce hydrogen for end uses not well served by direct electric power, such as some kinds of marine, rail, off-road, and heavy-duty truck transport.

Wow! What a vision for the future! Naturally the article raised a storm of counter-arguments from detractors, and a wave of support from the (green) dyed-in-the-wool pro WWS lobby. I won’t rehearse the pros and cons of the responses to this article, but the fundamental issues appear to be that the authors are not proposing a plan or road map to achieve the WWS scenario by 2030, but a set of possible milestones we should examine and perhaps try to move towards. Others say that the challenge of movement of power generated across countries and continents is understated, and that WWS works mist efficiently when it is locally generated power used by local communities. Finally, the will of nations’ leaders to join together and share in not just the vision itself, but the practical implementation, cannot be underestimated.

But whatever views you and others may have on this, I say that it’s a welcome addition to the debate on renewable energy on a global stage.